30 Years of Strengthening the Direct Care Workforce

In 2021, PHI began celebrating our 30th anniversary.

Amidst this year’s historic progress for direct care workers, we take pride in looking back and knowing that PHI has been at the center—and in many cases, in the lead—of significant advances for the direct care workforce.

During the past three decades, we have been honored to work with numerous inspiring workers, older adults, people with disabilities, organizations, employers, policymakers, and other advocates to move the needle on the direct care workforce. Today’s victories are the direct result of these efforts—and yet, we have so much work ahead of us to transform this essential workforce.

Here are some of PHI’s most memorable achievements for the direct care workforce over the last 30 years.

1991

PHI (then known as the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute) is formed as the non-profit partner of Cooperative Home Care Associates (CHCA), a first-of-its-kind worker-owned home care agency in the South Bronx. PHI focuses over the next decade on operating CHCA’s entry-level training program and supporting the creation of other home care cooperatives, including Home Care Associates in Philadelphia (1993) and Cooperative Home Care of Boston (1994-1999), while expanding employee-centered models in Detroit and New Hampshire.

As it grows, PHI cements itself firmly as the nation’s leading expert on the direct care workforce, rooted in the belief that quality direct care jobs are the foundation for delivering quality care. In the decades that follow, other organizations begin to advocate for direct care workers as well. This constellation of organizations at all geographic levels, including an extensive network of state and local groups, has particularly flourished in recent years, reflecting the direct care workforce movement’s growing importance and effectiveness.

2000

With the first major federal grant or contract to support direct care workers, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) funds the establishment of the National Clearinghouse on the Direct Care Worker, a historic online resource of publications on the direct care workforce. PHI and the Institute for the Future of Aging Services (now known as the LeadingAge LTSS Center @UMass Boston) co-lead this initiative, which is instrumental in raising early awareness in this country about the critical role of direct care workers. The clearinghouse evolves into the National Direct Care Workforce Resource Center, as relaunched and updated by PHI in 2020, which now serves as the country’s premier online library of information on these workers.

2002

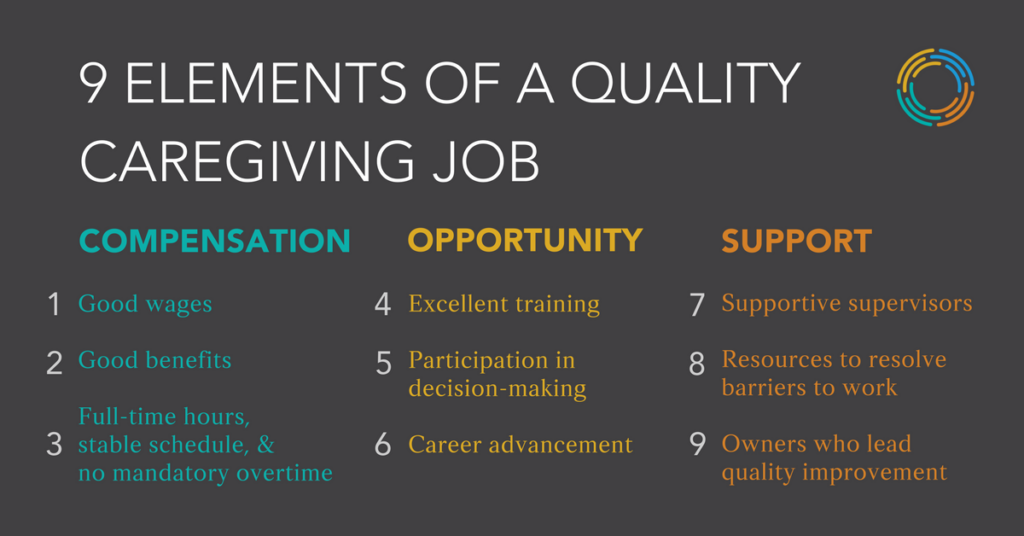

A 4-year initiative (“Better Jobs Better Care”) led by PHI and the American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging (now known as LeadingAge) demonstrates the correlation between quality direct care jobs and quality care. This major initiative also produces a new framework for promoting job quality in direct care. Organized across three dimensions—compensation, opportunity, and supports—The Nine Elements of a Quality Job Caregiving Job is a seminal framework in the long-term care sector, shaping workforce interventions, public policy, and research in the many years that follow.

As evidence of some of the earliest federal investments in direct care workers, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) funds PHI to produce a series of publications to help state agencies, providers, and individual consumers recruit, train, and retain home care workers. Three years later, HHS again funds PHI and the Institute for the Future of Aging Services to create a collection of papers exploring public policies and industry practices related to recruiting and retaining direct care workers.

2006

CMS establishes the Direct Service Workforce Learning Collaborative and the National Direct Service Workforce Resource Center to develop innovative strategies for the direct service workforce (i.e., direct care workers). The Lewin Group coordinates these activities and works with organizations like PHI and the Center for Applied Research (no longer active) to develop a range of online resources and provide technical assistance to state leaders on how to strengthen this workforce.

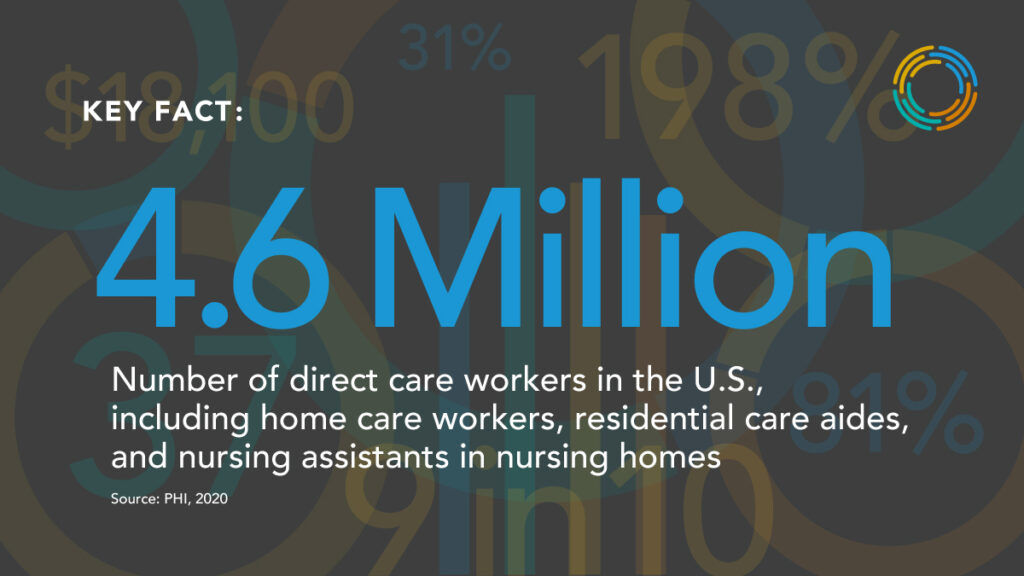

PHI begins publishing detailed data on the U.S. direct care workforce, giving policymakers and industry leaders unprecedented, up-to-date figures on this workforce while creating several benchmarks to assess how this workforce changes over time. The latest version of this research, Direct Care Workers in the U.S.: Key Facts, is released in September 2021.

2008

The Institute of Medicine (IOM; now the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine) releases a groundbreaking report, Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Healthcare Workforce, which investigates the readiness of our country’s health care workforce to support a growing population of older adults. The report includes an extensive chapter on the direct care workforce—informed by PHI at the request of IOM—and recommends that the federal government set minimum training requirements at 120 hours for home health aides and nursing assistants while also recommending that states establish some type of training standards for personal care aides. Retooling for an Aging America also calls for improved compensation, training, career advancement, and more for these workers.

2009

In response to Retooling for an Aging America, PHI and the American Geriatrics Society establish the Eldercare Workforce Alliance to jointly advocate for policy solutions that strengthen the long-term care workforce. Originally comprised of 25 member organizations, the Eldercare Workforce Alliance now includes 35 national organizations representing consumers, family caregivers, the direct care workforce, and other health care professionals.

Through the National Direct Service Workforce Resource Center created by CMS and coordinated by the Lewin Group, PHI authors a report recommending a first-ever national minimum data set on the direct care workforce. The Need for Monitoring the Long-Term Care Direct Service Workforce and Recommendations for Data Collection recommends that workforce data be collected to measure at least three core areas: workforce volume (i.e., the number of part-time and full-time workers), workforce stability (i.e., turnover rates and vacancies), and worker compensation (i.e., wages and benefits).

2010

As part of the Affordable Care Act, the federal government launches the Personal and Home Care Aide State Training Demonstration Program (PHCAST), which supports six states in adapting and scaling competency-based personal care aide training programs. The six PHCAST states—California, Iowa, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, and North Carolina—develop programs that collectively train approximately 4,500 new and incumbent direct care workers over three years. PHI plays a lead role in designing the federal PHCAST program and provides technical assistance to PHCAST initiatives in four of the six states (California, Massachusetts, Michigan, and North Carolina) to advance the field for all personal care aides entering the field. Though evaluation methods vary across the states, PHCAST trainees overall report high levels of satisfaction with the program and increased knowledge due to the training. Each state also reports that PHCAST strengthened its overall training capacity.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) adopts PHI’s recommendations to redefine federal occupational titles and definitions for key groups within the direct care workforce, including personal care aides, home health aides, and nursing assistants. Eleven years later, as the understanding on this workforce has evolved, PHI recommends that OMB work with long-term care and workforce experts to update these codes so that they characterize the direct care workforce more accurately. PHI and other advocates specifically call on OMB to establish a Direct Support Professional Standard Occupational Classification code to distinguish these workers from nursing assistants, home health aides, and personal care aides.

2011

PHI publishes the groundbreaking report, Caring in America: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Nation’s Fastest-Growing Jobs: Home Health and Personal Care Aides, which describes the state of home care workers and their employers, as well as the complex service delivery systems supporting older adults and people with disabilities.

PHI launches an online workforce data center that allows state and federal leaders, researchers, advocates, and others to access customized data on the direct care workforce. As of 2021, thousands of online users per year download up-to-date state and national snapshots on the direct care workforce, including data on demographics, job characteristics, and projected job openings.

Drawing on extensive guidance from PHI, CHCA, Independence Care System (ICS), and several model employers in New York City, New York State enacts the New York State Home Care Worker Parity Law, which establishes minimum compensation requirements for Medicaid-funded home care workers, creating “wage parity” among various types of home care workers in New York City and Nassau, Suffolk, and Westchester counties.

In the years that follow, New York State and New York City—like many other parts of the country—enact various laws that exemplify how states and localities can advance direct care workforce reforms. Some notable actions include creating the Office of Labor Policy & Standards for Workers in New York City (2014), establishing an Advanced Home Health Aide job category for home health aides (2016), and forming New York City’s Division of Paid Care (2016) to provide outreach and support to home care workers (and child care and other domestic workers), among other responsibilities.

2013

As a result of years of collective advocacy by numerous national and state organizations, including PHI, the U.S. Department of Labor issues a federal rule that extends wage and overtime protections under FLSA to more than two million home care workers nationwide. The initial rule relies heavily on PHI’s research and analysis. After a court delay and two years of grassroots organizing, the rule goes into effect in October 2015.

The Community Living Assistance Services and Supports Act (CLASS) Act that was created by the Affordable Care Act is determined to be financially unsustainable and repealed, ending the first federal social insurance program for long-term services and supports (LTSS)—before implementation begins. Several years later, in 2019, the National Academy of Social Insurance issues a historic report on “universal family care,” a social insurance policy framework for states to better fund LTSS, childcare, and paid family and medical leave. PHI issues a companion report on designing state-based social insurance programs in LTSS to support direct care workers. The same year, Washington State enacts the LLTSS Trust Act, becoming the first state in the country to adopt a state-based social insurance program in long-term care. Then in 2021, Congress introduces the Well-Being Insurance for Seniors to be at Home (WISH) Act, which aims to create a federal social insurance program in long-term care.

2015

In support of an ongoing court battle regarding the 2013 federal FLSA rule, 27 organizations, including PHI, submit an amicus brief arguing that home care work requires a broad range of competencies and significant training that go beyond “companionship services,” which underscores why these workers deserve wage and overtime protections under FLSA.

PHI, ICS, and three home care agencies collaborate to create the Care Connections Senior Aide role, an advanced role in home care that provides extensive training and enhanced compensation for home health aides. These senior aides help improve care transitions, solve caregiving challenges in the home, and serve on consumers’ interdisciplinary care teams. This demonstration project results in an 8 percent reduction in the rate of emergency room admission among the 1,400 consumers impacted, reduced caregiving strain among family members, and improved job satisfaction among home care workers, among other impacts. Throughout the decades, leaders across the field design numerous other direct care workforce interventions, such as training and advanced role programs, matching service registries, pipeline-development approaches, immigrant-focused supports, and much more.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine appoints PHI to its Forum on Aging, Disability, and Independence, strengthening the direct care workforce perspective on the Forum’s influential activities and thought leadership.

2017

PHI launches #60CaregiverIssues, a 2-year public education campaign based on 60 concrete ideas from PHI for addressing the workforce shortage in direct care. Roughly every two weeks, for two years, PHI releases a new recommendation to address this shortage. The social media campaign spurs significant media coverage and online dialogue, inspiring policymakers to begin creating multi-issue policy interventions for direct care workers across a range of areas. In 2018, the Academy for Interactive Visual Arts awards PHI a Communicator Award, the largest and most competitive awards program honoring creative excellence for communications professionals.

PHI issues the first comprehensive federal priorities report focused exclusively on direct care workforce policy concerns. This report provides analysis and recommendations across five areas critical to this workforce, including wages and benefits, training and advanced roles, data collection and quality, access and cultural competence, and family caregiving.

Amid an increasingly contentious national debate on immigration, PHI releases a first-ever statistical snapshot of the immigrant direct care workforce, which shows that one in four direct care workers is an immigrant, totaling more than one million workers nationwide. The study goes viral, spurring news stories in The New York Times, Kaiser Health News, and many other prominent media outlets nationwide.

HHS hosts the first-ever National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers, focusing one of its 12 recommendation themes on building workforce capacity to support persons with dementia and their caregivers. As part of the second dementia care summit in 2020, PHI co-chairs the Workforce Development Workgroup, which arrives at 10 workforce development recommendations to improve the research and evidence base on the dementia care workforce, including direct care workers.

2019

In partnership with researchers from the Harvard Medical School and Health Policy Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, PHI releases an in-depth report outlining a vision for strengthening the home care workforce and improving home care access and quality, along with evidence-informed recommendations for achieving this vision.

2020

The COVID-19 pandemic emerges, disproportionately impacting essential workers (such as direct care workers), older adults, people with underlying conditions, and communities of color, among other at-risk groups, and claiming more than 700,000 lives in the U.S. between March 2020 and October 2021. From day one of this health crisis, PHI begins tracking the pandemic and analyzing its impact in LTSS, joining sector-wide workgroups and national webinars, issuing articles and surveys, and providing guidance to employers and policymakers on responding to this unprecedented virus. In October 2020, PHI releases a report on job quality among direct care workers, focusing on the effects of COVID-19 on this job sector.

COVID-19 reinforces and amplifies the longstanding challenges facing direct care workers related to compensation, training, advancement, data collection, and staffing while surfacing new difficulties related to safety (including access to personal protective equipment and other supplies) and vaccine acceptance. An estimated 280,000 direct care workers leave the sector within the first three months of the pandemic. An estimated 342,000 direct care jobs are lost from February through December 2020. Although workforce numbers begin stabilizing by early 2021, few displaced workers are re-employed in direct care jobs, turnover in this job sector remains high, and long-term care employers around the country continue to experience severe staffing shortages that threaten their ability to stay afloat.”. In the midst of such catastrophe, this workforce experiences a few positive advances: the visibility of these workers grows considerably; several states enact temporary measures for these workers, such as hazard pay and emergency leave; and a new federal administration enacts the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, which helps states cover the cost of major direct care job improvements.

PHI releases a new framework, The 5 Pillars of Direct Care Job Quality. To guide employers, policymakers, and industry leaders in transforming the direct care workforce, this new framework for direct care job quality includes 29 elements across five pillars: quality training, fair compensation, quality supervision and support, respect and recognition, and real opportunity.

2021

On the eve of a new presidency, PHI releases Caring for the Future: The Power and Potential of America’s Direct Care Workforce. A follow-up to the organization’s 2011 report, Caring in America, this report offers an unparalleled, in-depth analysis of the direct care workforce with an extensive list of policy and practice recommendations across eight issue areas. In July 2021, PHI builds on this framework when it releases a federal priorities report with nearly 50 concrete recommendations for the White House, Congress, and key federal departments and agencies, solidifying its role as the top technical expert on direct care workforce policy and practice. (PHI wins another Communicator Award for the Caring for the Future report and campaign in the category of integrated communications campaign).

The Health, Employment, Labor, and Pensions Subcommittee and Higher Education and Workforce Investment Subcommittee under the U.S. Committee on Education and Labor hold a Congressional hearing on the challenges facing direct care workers and how federal leaders should respond. At the hearing, Congressional leaders discuss the merits of recent federal proposals on this workforce, including the Direct CARE Opportunity Act, which would invest more than $1 billion over five years in interventions that improve direct care workforce training, recruitment, and retention.

PHI joins the Care Can’t Wait Coalition, which is formed to help realize the Build Back Better investment in the care economy, co-led by 15 organizations, including Care in Action, SEIU, MomsRising, Paid Leave 4 All, the National Domestic Workers Alliance, and several others. Throughout the year, the coalition coordinates sign-on letters, rallies, virtual town halls, social media campaigns, meetings with constituents and elected officials, a $2 million advertising blitz in support of the Build Back Better reconciliation package, and much more. Public opinion seems to be on the side of this historic investment; a September 2021 poll in 12 key states finds that most likely voters support the “build back better” agenda.