The Economic Case for Improving Direct Care Jobs

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted and reinforced the essential role of direct care workers. Alongside other health and long-term care professionals, these workers support the health and wellbeing of millions of older adults and people with disabilities. And just like those other professionals, they deserve good jobs that reflect their enormous value and allow them to achieve financially security.

To help realize this ideal, the Biden-Harris administration has proposed a significant funding boost that would greatly improve jobs for all direct care workers and strengthen the overall care economy. Why do direct care jobs need this major investment? Because, although direct care is essential, complex, and skilled work, direct care jobs are often characterized by poverty-level wages, inadequate training and advancement opportunities, and an overall lack of recognition and support. Poor job quality also undermines the ability of long-term care employers to fill these jobs, respond to growing demand, and meet their bottom lines. In turn, older adults, people with disabilities, and family caregivers struggle to access the services and supports they critically need.

A less-frequently acknowledged reason for investing in direct care jobs is that it would also bolster our national, state, and local economies. Direct care job quality and economic development go hand in hand, as underscored by experts in this field and a growing body of research. Here are four clear ways that improving direct care jobs also makes good economic sense.

DECREASING PUBLIC ASSISTANCE EXPENDITURE

Forty-seven percent of direct care workers rely on some form of public assistance, including 29 percent who access Medicaid, 26 percent who receive food and nutrition support, and 3 percent who benefit from cash assistance. These measures help low-income families survive and even move out of poverty; in 2019, researchers estimated that these types of economic security programs reduced poverty among Americans by half since 1967. In fact, U.S. poverty would have been nearly twice as high in that period if not for these programs.

However, the total cost of these programs is sizable. Federal spending related to Medicaid ($613.5 billion), food and nutrition support ($92 billion), and cash assistance ($16.5 billion) currently totals about $722 billion. Investing in direct care jobs would help decrease these safety net expenditures by reducing poverty. LeadingAge has estimated that raising direct care wages to a living wage would reduce the percentage of direct care workers using public assistance (defined more broadly to include housing subsidies and the earned income tax credit, as well) by 16.8 percent, which would translate to a savings of $1.6 billion.

Similar results have been estimated across the entire workforce. The Economic Policy Institute recently calculated that increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, as one example, would reduce annual public expenditures on the earned income tax credit and the child tax credit by about $20 billion. This wage increase would also reduce annual expenditures on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program by $5.4 billion.

STIMULATING CONSUMER SPENDING & JOB GROWTH

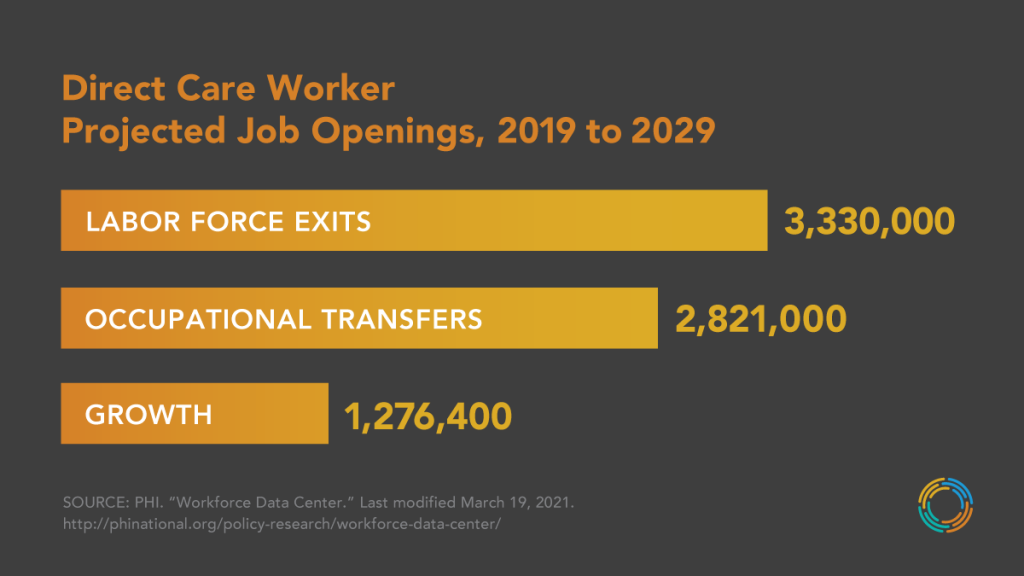

Increasing wages for direct care workers would also promote consumer spending, benefiting the entire economy. The analysis cited above also showed that providing direct care workers with a living wage would increase their contribution to the economy by $17 billion to $22 billion (from 2022 to 2030). In the same time frame, this economic growth would in turn create more jobs across sectors—anywhere from 65,000 to nearly 86,000 additional jobs. In contrast, as the figure below demonstrates, poor job quality left unaddressed will contribute to the projected 7.4 million job openings in direct care between 2019 and 2029, notably the millions of job separations caused by workers who leave this occupation or exit the labor force.

REDUCING COSTLY TURNOVER

Because of poor job quality and a dearth of effective recruitment and retention measures, many direct care workers are driven out of this job sector. As the figure above demonstrates, more than 2.8 million direct care workers will move into other occupations—contributing to a total of 7.4 million job openings in this sector within a decade (from 2019 to 2029). Turnover within direct care occupations is also persistently high, estimated at 65 percent for home care workers and 99 percent for nursing assistants—and this instability in the workforce is very costly for employers. The estimated cost of employee turnover in senior care is $3,500 to $5,000—a total cost that amplifies when accounting for every employer and state in this country grappling with the constant departure of workers. In contrast, increased employee retention can boost morale and productivity, enhance care, and limit training and recruitment costs, among other benefits.

SAVING HEALTH CARE COSTS

Direct care workers support individuals in maintaining their optimum level of health at the lowest cost—helping avoid costly health outcomes such as emergency department visits, avoidable hospitalizations, early nursing home admissions, and more. Enhancing direct care training and developing advanced roles for experienced workers can amplify this contribution, as well as help prevent injuries, accidents, and malpractice suits (for a workforce that has some of the highest rates of occupational injury in the country). Beyond these immediate costs savings to the health care system overall, a federal investment in upskilling and advanced role interventions in direct care would generate an evidence base for future replication and scale-up, which would lead to greater savings over time.

CONCLUSION

Already, the direct care workforce is larger than other single occupation in the country—and it is projected to add more new jobs than any other occupation within the decade ahead. This fact reflects the profound need for these workers as the U.S. population continues to age rapidly. It also speaks to the centrality of these workers to so many people and our economy.

Biden’s proposed investment in expanding home care access and improving jobs for home care workers is monumental and sorely needed. As this plan acknowledges, these workers need an array of federal strategies to improve their jobs, such as increasing compensation and financing, strengthening training and advancement opportunities, building the data collection infrastructure, rectifying racial and gender inequities, and more.

It’s rare for federal leaders to have an opportunity to enact a historic, sweeping measure that benefits everyone. But this plan might be the one.