Systemic racism has long harmed the lives and jobs of people of color in direct care—from the creation of these poor-quality jobs, through the decades-long exclusion of home care workers (and other domestic workers) from federal wage and overtime protections, to the widespread racial discrimination that people of color and immigrants continue to face regarding employment, housing, education, and health care, among others. Additionally, caregiving has historically been defined as “women’s work” and is still often dismissed as a labor of love that requires only minimal compensation and support, perpetuating poor job quality in this sector. Finally, the political climate has become increasingly hostile to immigrants in recent years, limiting targeted supports for immigrants who are a critical part of this workforce. Despite these various challenges, policy and practice interventions aimed at direct care workers do not often account for the unique structural barriers and inequalities they face on the job and in their daily lives, limiting the evidence base on race and gender-explicit workforce interventions in this sector. When focusing on direct care workforce development, we must center and uplift women, people of color, and immigrants—these workers deserve good jobs rooted in equity and justice.

RECOMMENDATIONS

To address the structural inequities that harm the lives and employment experiences of direct care workers who are women, people of color, and/or immigrants, we recommend the following:

Develop strategies to address systemic barriers and strengthen diversity, equity, and inclusion within this job sector. To ensure that women, people of color, and immigrants (among other marginalized groups) can succeed in these roles, employers must design interventions that explicitly target the systemic barriers these workers experience. A critical step is to collect gender and race-related outcomes data across various job quality indicators in order to identify and address disparities in recruitment, hiring, retention, and other workforce outcomes.

Build the evidence base on equitable direct care workforce interventions. Interventions focused explicitly on supporting marginalized segments of the direct care workforce should be adequately funded and evaluated to help build the evidence base on equity in this job sector. Further, as workforce development leaders and other innovators design and test new interventions for direct care workers (related to training, advanced roles, and more), they must evaluate whether women, people of color, and immigrants benefit equally from these approaches—in the short and long-term.

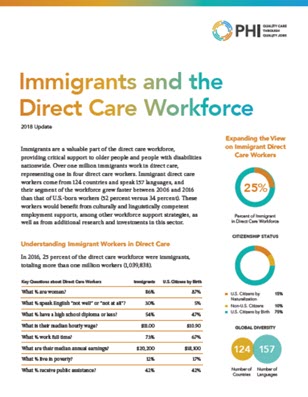

Bolster supports for immigrant direct care workers. Immigrants are a significant part of the direct care workforce, and they need targeted supports to make it easier to fulfill their roles. These workers would benefit from more research to understand their unique challenges, public policies that address their recruitment and employment needs, culturally and linguistically competent workforce supports (especially for workers with limited-English proficiency), stronger access to community-based resources (legal and housing assistance, etc.), and a pathway to citizenship.